|

Dialogical singing was widely practiced in Lesbos until the early 1960s [23]. And so was the dialogical ghlendi, the performative whole to which dialogical singing belonged as a distinct yet indispensable part.

Another case in point is the dialogical ghlendi that was performed at the kouitoukia of Aghiassos, a big village to the north of Plomari. The kouitoukia were small coffee-places that were scattered all over the village area. These were rough outdoor structures which operated usually on Sundays and feast days.r and, at the same time, as a timely and accurate expression of social experience.

Dancing in front of the church; Boros (Lesbos), 1953. (Dionysopoulos ibid: 69) The kouitoukia were very popular sites for socializing, as they were fully integrated with the everyday culture and social life of the village. The dialogical singing that was performed in front of these rough structures was greatly appreciated by all the inhabitants of Aghiassos, especially the young male revelers of the ghlendi and the young girls to whom most of the songs were addressed. The dialogical ghlendi at the kouitoukia was a symbolic domain that enabled the young people of the village to express themselves in public and negotiate the boundaries of some real or imaginary personal concerns. In its space, the male singers and the girls who lived in the neighborhood where the ghlendi was held were allowed to get together and communicate their feelings of sympathy and love for each other without violating the social norms of their culture regarding gender relations.

Dialogical singing is a constitutive element of the

dialogical ghlendi. Such a form of singing is constituted by the

experience of the dialogical reality of the ghlendi whole and is,

at the same time, a constituting modality that is conducive to the

performative realization of the dialogical principle as such. If the

idea of the dialogic is not reduced to the act of conversation, but is

understood literally as a juxtaposition of various logics, it might then

be contrasted to the idea of the monologic,

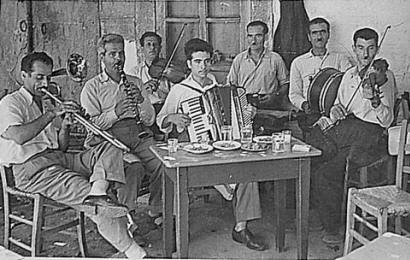

A post-War musical band; Kapi (Lesbos), 1957.

(Dionysopoulos

ibid: 37)

Its coexistence with the longstanding tradition of the dialogical

ghlendi prepared the ground for various fusions of the monologic and

dialogic elements on the level of both music and culture. A case in

point is the effect that brass wind bands had on the dynamics of the

dialogical ghlendi experience. With their overwhelming sound,

these bands made non-amplified singing impossible, helping thus to

solidify specialization in musical performance.

The Feast of the Archangels;

Parakila (Lesbos), early Fifties. (Dionysopoulos ibid: 123)

The brass wind bands played a significant

role in helping to establish a structural distance between the

performer and his audience as maker of music and listener. Such

performances were conducive to a gradual monologization of the

dialogical component of the ghlendi both in music and

culture.

The ghlendi of Lesbos

acquired a monological quality which gradually became the

defining element of its social performance. This was the case up

until the mid 1990s, when a new expression of the monologic in

association with the performance of

|