|

The projects of Turkish Roman clarinetist Hüsnü Şenlendirici demonstrate yet another reconfiguration of Roman identity, in this case through the crucible of enlarged transnational music markets. Hüsnü’s projects have been sponsored under the management and enlarged vision of the music company

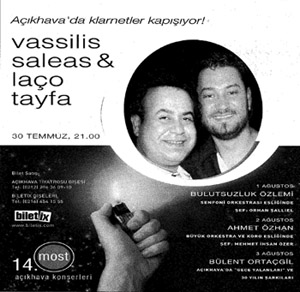

In 1998, I facilitated Hüsnü’s initial signing on to Pozitif for a collaborative recording and concert project. This first project brought artists from the Brooklyn Funk Essentials to Pozitif, who in turn approached me to find Roman artists who could fuse Roman wedding music with elements from jazz, funk, reggae and other contemporary popular genres. Having worked closely with this musician family, I recommended Hüsnü Şenlendirici based on my knowledge of his background and training with his father, Ergun. In long-distance consultation with Hüsnü, who was serving in the army at the time, and his family members, I constructed the first configuration of a group around Hüsnü’s talents. For this group I proposed the name, “Laço Tayfa” meaning “Good group” which derives from Romanes (laço meaning “good”) and Arabic (tayfa designating a work group). [33] Thus this project was in part shaped by field of ethnomusicology through the discursive practices of a US-trained ethnomusicologist, as well as by Turkish and Roman imaginings of cosmopolitan local musical practices as “world music.” After the success of this first album, In the Buzzbag, Pozitif supported a second recording project under Hüsnü’s vision and control, which resulted in the CD, Bergama Gaydası (Gayda [a type of instrumental dance form, popular among Roman] from the town of Bergama). Discussions with Hüsnü during the pre-recording planning were illuminating as to the musical negotiations of complex local and transnational discourses. For this second project, Hüsnü wanted to work from inside Turkish and Roman traditions, mediated with layered sounds, pop textures and incorporation of funk, reggae, and other distinctive chordal rhythmic structures. Adopting some of the musical strategies from the previous project, he revealed that he sought to appeal to “Western” (European and American) audiences, and also present sonic clashes to Turkish audiences that would anticipate familiar treatments of well-known material, and be caught off-guard by his new rhythmic and chordal arrangements. As he related to me, “I want people in the audience to start dancing [because they know the piece], but then stop short and say, ‘What’s going on here?’” For Hüsnü, however, musical inclusion of Roman ethnic music was problematic. By the 1990s, regional Roman wedding music was so tightly linked with pan-Roman identity that Hüsnü initially did not want to include any Roman music on the recording. “Any one can pick up a clarinet, violin, drum and cümbüs and play (wedding) music like that. That’s not ME” (Şenlendirici 1999: pers. comm.). His decision to include two wedding tunes implicates my own role in bringing in my perception of strategies within US-Western European “world music” market. I felt strongly that this genre had a great deal of appeal and expressive power, and also felt that while he was expressing “Turkish” regional identities, there should be a place to invoke his own identity and that of the members of his ensemble. In suggesting that he consider adding a 9/8 meter Roman oyun havası to his CD, I drew on the role Hüsnü had given me as an advisor with a “Western” perspective, and also our shared knowledge that Roman music was of interest to Western European and American world music audiences. Among the two Roman pieces included on this CD, Bazalika, is telling for its complex referencing of Western European pop, jazz, and local Roman musical elements. The title itself encodes multiple local and transnational references, aimed at tourist audiences. “Bazalika” (“Basillica”), refers to a well-known Greco-Roman historical and tourist site in Hüsnü’s home town of Bergama, and a site which employs many young men from the Roman neighborhood. It is also a locale for key Roman ritual events, such as washing henna from the bride’s hands and feet. Musical references also embed Roman, Western European elements aimed at transnational audiences. Hüsnü embedded the iconic musical features which signal Roman identity by balancing studio arrangements in the ensemble sections against the wedding-style performance in the improvisatory solo section. He arranged the main melody in a Turkish pop music style in a texture dominated by clarinet over a bass guitar, and trap set sound. The main melody was loosely based on motivic figures from Ahmet “Ciguli” Popov’s “Agam” (see sound example #1), with sophisticated chords, movement in parallel octaves, surprising rests, and an overall tight orchestral arrangement.

this local sonic affect, during this session he exhorted the musicians to play their best by reminding them about the experience of playing weddings in the neighborhood, late at night and early into the morning, past the point of exhaustion in which all the music comes together. Thus he avoided perceived Roman parochialism through the iconic condensing of Roman sonic symbols of Roman wedding style (timbre, texture, melodic motives) into a pop-synthesized texture. Through this process, Hüsnü effectively performed a musical statement of being Roman in the place world of Roman neighborhoods, while also expressing a belonging that extends beyond Turkish borders.

were a mix of instruments associated with Ottoman light classical urban music (kanun, violin), pop music (synthesizer, electric guitar), and rural folk genres (bağlama). During the next hour the ensemble played arrangements that followed their recorded tracks from their most recent CDs to wildly applauding fans.

Europe. The Roman stylistic inflections and improvisations also had the effect of added local exotica to the mix by musically referencing and re-creating “the other from within” (cf. Pettan 2001). By 2003, this new sonic mixture was not only available in large public venues, and in record shops in Europe, Canada, and the US, but had also been incorporated back into Roman communities. During the summer of 2003, Laço Tayfa’s “World music” arrangements of Roman wedding tunes and regional songs from the Aegean southwest were being adopted by Roman wedding bands in the Thracian Northwest. In addition, young wedding clarinetists sought to increase the use of the upper register of their clarinet, emulating Hüsnü’s characteristic solo style. The in-community circulation of this new type of repertoire among Roman wedding bands is indicative of the local appropriation of changing transnational economic circuits, translated back into local meanings. |