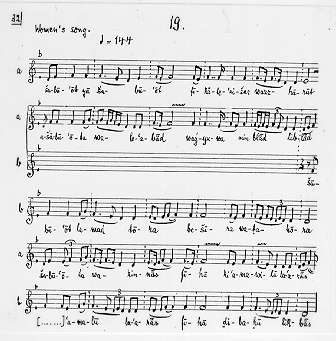

Both time and place gender the musics of the Jewish Mediterranean. The gendering impact of time is the product of and the basis for history, that is, for Jewish history as a composite thread within and inseparable from the larger history of the Mediterranean as a whole. The gendering impact of place maps that history on the musical landscape of the Jewish Mediterranean. History and geography coexist on this Jewish musical landscape, but they do so only in a contested relation, and Jewish music, because of its inextricability from the secular and sacred presence of gender, undergirds that relation. In the Jewish historical imagination spawned by diaspora the journey to the East, to the Eastern Mediterranean, produces the return to a timeless past, that is, an unchanged and unchanging world of Jewishness and a Jewish music that embodied timelessness and placessness (cf. Bohlman 1997). This is what ethnomusicologists hoped to find when they began to collect Jewish music in the Mediterranean during the era of Jewish music collection at the turn-of-the-century. By returning to and gathering up Jewish music in Mediterranean communities, A.Z. Idelsohn, Robert Lachmann (Lachmann 1976), Friedrich Salomo Krauss, and Alberto Hemsi (see Hemsi 1995), believed they might suture the diasporic gap between Jewish music as it was believed to exist at a moment of biblical authenticity and as it was sustained in an historical stasis, always already Jewish in the Mediterranean world. Instead, when they bounded Jewish music in traditional terms (e.g., in the synagogue, connected to Jewish practice and in Hebrew), they found that women' music failed to confirm the survival of an authentic Jewish music. Undermining theories about the unity of the Mediterranean was gender, more specifically, the reality that women' music, though clearly anchored to local Jewish communities and ritual, failed to possess the criteria of Jewishness, such as large repertories utilizing the sacred language. To remedy this dilemma, women' music received its own space in the geography and history of Mediterranean Jewish culture, a secular space, indeed, an exotic and sensually orientalized space. I should like to turn briefly to a case-in-point, in fact, the classic Jewish community imagined musically to connect the past to the present: the Yemenite community and Yemenite-Jewish music. In the modern Jewish imagination of the diaspora, Yemen&mdashboth because of its isolation at the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula and because of its location on significant trade routes between Europe, Africa, and Asia, which in turn spawned highly gendered myths, such as that of the Queen of Sheba&mdashhas been the site of a type of authenticity that draws sharp lines between Jewishness and otherness. Early ethnomusicologists and music collectors, for example A.Z. Idelsohn in the first volume of his Thesaurus of Hebrew-Oriental Melodies (1914), devoted their collections primarily to the music of men, drawing attention to the repertories of the synagogue, to the boy' school, or cheder, and to the diwan, a secular space in which repertories with classical Hebrew and Arabic genres were performed, often woven into the same songs. Yemenite Jewish women sang in the vernacular, that is, in Yemenite Arabic or in the Judeo-Arabic of Yemen. Judeo-Arabic functioned in Yemenite music, therefore, in ways quite similar to ladino in Sephardic songs. Women did not sing in the synagogue, cheder, or diwan, but rather used song in ritual settings, especially those in rites of passage&mdashnotably weddings&mdashand in the liminal community spaces between Jewish and Muslim cultures. The world of male song is that of the sacred and the spiritual self. The world of women' music is that of reproduction and the physical body. The music of men is expressive through prayer and poetry. The music of women is expressive through social intercourse and dance. The next example is a Yemenite Jewish song from the diwan, hence from a men' space concentrating the high culture of the masculine strands of history. The text of the song is in the form of a dialogue between the poet and his beloved, hence allegorically about the return from exile to Jerusalem. Linguistically and thus historically, Self and Other are clearly marked in the composed genre known as shirah, for some strophes are in Hebrew and others (the third and fourth) in Arabic, though both are literary forms of those languages set in classical poetic meters. Whereas the men' song draws Yemenite Jewish culture inward, toward a historicized identity centrally located in the diwan, the women' song in the next example projects a movement outward, beyond the peripheries of the tradition, genre, and community. Sung by popular singer, Ofra Haza, "Take 7/8" also recognizes and represents gendered musical practices, such as the asymmetrical metric pattern announced in the song' title, which in turn are unmistakably hybridized, for example, in the stereotyped use of kerosene cans as percussion instruments in Yemenite Jewish music. In the CD liner notes, the text in Judeo-Arabic is prefaced with the following comments, which render the spaces of ritual and reproduction unambiguously feminine: "A special rhythm in 7/8. / We used to dance to it. / Especially in wedding parties / Only women then, / But today "all together."

These distinctions, canonized at the time of the first encounters with Yemenite-Jewish music, are no less vivid and evocative in postmodern iconography and representations of Yemenite-Jewish music today. Collections of Yemenite Jewish songs, therefore, announce themselves by using covers with women, often anonymous and faceless, dressed for a wedding, draped with orientalizing jewelry. Popular Yemenite Israeli singers, such as Ofra Haza, are represented in similar ways on CD and album covers, though not without an added heightening of sexuality. The various forms such sexuality takes at once confirm and confuse the hybrid, feminized representation of Jewish culture in traditionally Arabic regions of the Mediterranean. Figures employing icons and representations of Yemenite Jewish Music

Music marks Mediterranen Jewish women as extraordinary and exceptional, but it does so by bounding an everyday world of difference. That this statement is deeply paradoxical is obvious, for we customarily define the everyday as that which is not exceptional. The everyday in Mediterranean Jewish society is nonetheless a domain of contact, exchange, and movement away from a presumably authentic core. The everyday also forms as a cultural zone of transgressing the borders between Self and Other. Quite specific genres of Mediterranean song emerge from the language practices of women and depend on the everyday, quotidian nature of those practices. A central practice in Iraqi-Jewish women' music, for example, is the embodiment and musical enactment of genealogies through pilgrimage (see Avishur 1987). Moroccan-Jewish women, too, are extraordinary for their worship at shrines to women saints, yet the veneration of these saints crosses gender lines, becoming normative (see Ben-Ami 1998). For Robert Lachmann, studying the Jewish communities on the island of Djerba off the coast of Tunisia, the discovery of "women' songs" provided the fundamental paradigm of otherness within Djerba society, but it eventually led him to critique and dismantle the historiographical paradigm of authenticity (Lachmann 1976).

The geographical and historical spaces of Mediterranean Jewish musics are therefore sharply gendered, but that sharpness belies the crucial contestation of the spaces. Specific genres come to represent those spaces and their contestation, for example, ballads and the narrative language of the Sephardic diaspora, ladino. A distinctive musical language takes shape within the spaces, as in the male religious education of the Yemenite cheder. The gendered nature of sacred musical practices, such as the network of pilgrimage shrines and routes across North Africa, remaps the Mediterranean itself as a gendered, Jewish landscape. The reference in my title to the "Jewish Mediterranean" is not a clearly bounded geographical or even religious region, which lends itself to representation on a musical map of some kind, but rather a means of drawing our attention to a series of histories that intersect in and around the Mediterranean, and convey those histories as fundamentally gendered and musical. |