| Gepriesen und geheiligt sei

ER inmitten Jerusalems. 25 Kantoren aus Jerusalem und umgebung (Jerusalem in Hebrew prayers and songs).

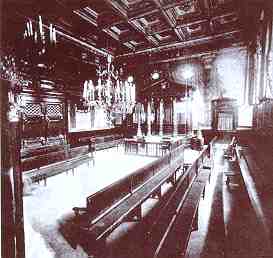

Produced by Jüdische Kulturtage and Haus der Kulturen der Welt in cooperation with Internationales Institut für traditionelle Musik. Program coordinator: Habib Touma. Program: Josef Ben-Israel. Academic consultant and program notes: Edwin Seroussi. Recorded and produced by Digital Bob Recordings, Daniel Rohde. CD 66.21201. The central place of the city of Jerusalem within Judaism hardly requires a demonstration. Regardless of whether the Jews themselves actually inhabited it, or rather longed to do so, such a centrality has been of key importance since the construction of the Temple in Biblical times, and particularly after the two occasions in which it was destroyed. The first destruction, in 586 BC, led to the mass deportation of the Jews to Babylon, while the second, in the year 70 CE, marked the beginning of the Jewish Diaspora. Both episodes led to a long history of exile that has partially come to an end since the foundation of the State of Israel fifty years ago. Before its destruction, the Temple of Jerusalem was the symbol of Jewish unity. The liturgy was celebrated with daily sacrifices administered by the priests (cohanim), while large numbers of Levites performed songs and instrumental music. The destruction of the Temple caused a complete reshaping of the religious cult. Daily prayers replaced the sacrifices, while the synagogues – once simply houses of study – became the only places of worship. Instrumental music was completely banned from all religious manifestation with the exception of the shofar, a horn mentioned in the Bible used on solemn occasions and for the gathering of the people at war. The shofar is still blown today on New Year's Day (rosh hashanah) and on the Day of Atonement (yom kippur).

The grandeur of the Jewish national past became extreme poverty in exile: the original unity gave way to a multiplicity of places and rites. All the principal aspects of Jewish life were structured around a place and an epoch that no longer existed in reality, but that had become an even more powerful pole of attraction from exile. Many new prayers, as well as liturgical and paraliturgical poems (piyyutim), were composed throughout Jewish history to celebrate Jerusalem from this perspective.

The only testimony of the former unity that was left to the Jewish people were the Five Books of Moses– the torah – which up to this day provide the basis for the religious, moral, and legal conduct (as well as the main source of inspiration for any artistic manifestation) within the traditional boundaries of the Jewish communities. The torah had been read in public – that is, in the towns, villages, and the marketplaces of Palestine – already since the fifth century BC, following a practice attributed to the Scribe Ezra. Out of this long-established custom originated the cantillation of the Hebrew text, which to this day constitutes the main performing practice of synagogue vocal music. The Jewish cantillation was set to a systematic order in the post-Talmudic period (i.e., after the sixth century CE) by a school of grammarians called massorah ("[transmitted] tradition"). These scholars established meticulous rules that govern the vocalization of biblical Hebrew, the syntactical ordering of the verses, and the distribution of a fixed number of melodic formulae among the words of the text. These rules are indicated by a system of signs called te‘amim (ta‘am means "taste" as well as "reason"), applied to the Hebrew text. Although they do give musical indications, the te‘amim are merely a symbolic reminder of the melodic formulae, and not a notation. The actual melodies used for the reading of the torah are part of an orally transmitted tradition. Moreover, the massorah – which plays a central role in synagogue song still today – was established long after the second destruction of the Temple, at a time when presumably most Jewish communities of the Diaspora had already developed autonomous melodic renditions of the torah that were often based on local, non-Jewish musical traits. Altogether, we can assume that the te‘amim system was not elaborated with the purpose of unifying the local musical traditions of each and every Jewish community, but rather as a unifying principle for governing the relationship between text and music. "Jewish music" as we know it today – without considering the music of the Temple, of which we only have literary accounts – is from its very origins a complex and variegated synthesis of local and distinct Jewish musical traditions that influenced each other only rarely, while they shared the same paradigm of the text/music relation codified by the massorah. Amongst the oldest musical traditions that still bear traces of how the torah was sung in ancient Palestine, we find today the sacred songs of the Samaritans. A small community (now reduced to less than one hundred people), the Samaritans have kept their traditions alive through time, thus creating a religion, language, and liturgy that closely resemble those of standard Judaism, while also differing from it on many a custom and exhibiting peculiar traits. One of their most powerful liturgical pieces is a polyphonic version of Moses’ song from the Exodus, Az yashir Moshe, sung at yom kippur.

The city of Jerusalem holds a special place in Jewish music for yet another reason. It was in Jerusalem that modern Jewish ethnomusicology was conceived by the eminent scholar Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (1884-1938). This could have happened only in modern Palestine, as a by-product of the Zionist movement that since the end of the last century had sought to reunify all the Jews of the Diaspora under a new nation in the ancient land of Israel. By the first decades of the 20th century, Jerusalem, which had never ceased to attract small numbers of Jews throughout the centuries, had become a haven for Jewish groups coming from almost every corner of the vast Jewish world. Only by carefully listening to the wide variety of Jewish musical traditions, all represented in the same city, was A. Z. Idelsohn able to conceive the extensive fieldwork and comparative study that culminated in a musical thesaurus (Hebräisch-orientalischer Melodienschatz, 10 vols., 1914-1932) and in a comprehensive book, Jewish Music in its Historical Development (1929).

Given the high social position that the ashkenazi (i. e. from central and eastern Europe) community has held in the state of Israel, and its large presence in the USA (despite being annihilated by the Nazis in Europe during WWII), its musical traditions are among the most "institutionalized" in the country. The liturgical repertoire has been codified and often composed throughout, during our century, by some very popular hazzanim ("cantors"), such as Yossele Rosenblatt (1880-1933) or Gershon Sirota (1874-1943). Cantor Shalom Rakovsky, from Jerusalem, is one of the finest and most learned performers of this repertoire, as he shows in one of Sirota’s most famous pieces (from the liturgy of the shabat), Retze Adonai elohenu be-amkha.

However, the ashkenazi traditions are altogether not the most relevant in Israel today. Many non-European traditions are extremely well represented, because their original context – implying a certain level of integration between the religious and the secular spheres – has been more easily preserved in the heart of the Middle East than the context of the European traditions. For example, the nearby Turkish tradition of sephardic origins (that is: from the Iberian peninsula, where Jews were present until they were expelled in 1492), but often based upon Turkish maqamat, is quite well preserved. The CD has a few tracks sung by the Turkish hazan Jakob Kohen, including a version of the hymn Lekha dodi (written in the 16th century by Rabbi Shlomo ha-Levi Alcabetz, from Saloniki), from the kabalat shabat liturgy of Friday night:

Very popular in today's Jerusalem is the ritual of the baqashot, that is, hymns and prayers performed at night during the weeks preceding the High Holidays (rosh ha-shanah and yom kippur). These ceremonies, which are full of mystical allusions, originated in Aleppo, Syria, but soon spread to Morocco, and eventually influenced the cabalistically oriented confraternities in 18th-century Italy. By the turn of the 20th century the baqashot had become a widespread religious practice in several communities of Jerusalem as a communal form of prayer. It included several performers and solo-singing alternating during the long performances, or in small choirs, as in the piece El mistater beshafrir cheviyon (by the cabalistic poet Rabbi Abraham Maimin, 17th century).

Finally, Jerusalem – or, in case a trip to Israel does not fit into the reader's plans, a CD like the one reviewed here – has become the most important place in which it is possible to hear some quite unknown, and very little popularized, Jewish musical traditions, such as the Kurdish one. This is well represented here by two songs, including the widely known (when set to non-Kurdish melodies, of course) sabbatical table song, or zemirah, Zur mi-shelo achalnu, as well as by melodies that became big "hits" in the general music market and are known to a much larger public.

Such is the case of the traditional song Im nin‘alu, based on a text of the Jewish-Yemenite diwan by Rabbi Shalem Shabazi (17th century) and made quite popular in the late 80’s as a dance song performed by the famous pop-singer of Yemenite origins Ofra Chaza.

Francesco Spagnolo Yuval Italia |

The creation of the State of

Israel in 1948 strengthened the cohabitation of a

multicultural Jewish population in the land. Distributed

in several immigration waves, Jews from every country

settled in the new State, also bringing their languages,

their customs, and of course their peculiar musical

traditions along with them. For many years, however, the

main concern of the newly founded nation was to provide

the immigrants with the basic standards of a common life

and to integrate them under the new identity of

"Israelis". This attitude often led the new

immigrants – such as the Yemenites and the Iraqis in

the 50’s and especially the Ethiopians in the

80’s – to neglect their traditions, that were

left for the elders of the communities to be preserved.

Only in more recent years did liturgical traditions

become a public concern, and received some of the

attention they deserved. The State of Israel is the only

place in the world where the widest variety of Jewish

musical traditions can be heard – usually by the

finest performers – within their original (or

originally reconstructed) context. As Edwin Seroussi

(Bar-Ilan University, Israel) underlines in his notes to

the CD Jerusalem in Hebrew Prayers and Songs,

"all the singers in this recording are genuine

representatives of their respective traditions, i.e.

either active cantors of synagogues or folk singers of

modern communities in Israel".

The creation of the State of

Israel in 1948 strengthened the cohabitation of a

multicultural Jewish population in the land. Distributed

in several immigration waves, Jews from every country

settled in the new State, also bringing their languages,

their customs, and of course their peculiar musical

traditions along with them. For many years, however, the

main concern of the newly founded nation was to provide

the immigrants with the basic standards of a common life

and to integrate them under the new identity of

"Israelis". This attitude often led the new

immigrants – such as the Yemenites and the Iraqis in

the 50’s and especially the Ethiopians in the

80’s – to neglect their traditions, that were

left for the elders of the communities to be preserved.

Only in more recent years did liturgical traditions

become a public concern, and received some of the

attention they deserved. The State of Israel is the only

place in the world where the widest variety of Jewish

musical traditions can be heard – usually by the

finest performers – within their original (or

originally reconstructed) context. As Edwin Seroussi

(Bar-Ilan University, Israel) underlines in his notes to

the CD Jerusalem in Hebrew Prayers and Songs,

"all the singers in this recording are genuine

representatives of their respective traditions, i.e.

either active cantors of synagogues or folk singers of

modern communities in Israel".