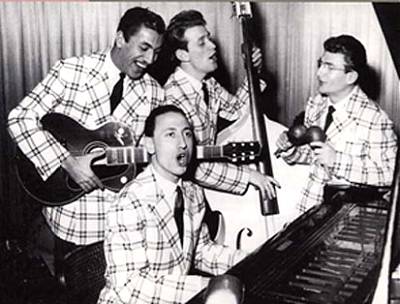

Towards the end of the 1950s the signs of change

manifested themselves strongly with the emergence of the

‘urlatori’, or ‘shouters’ (the name

that the critics of the time gave to local rockers), and

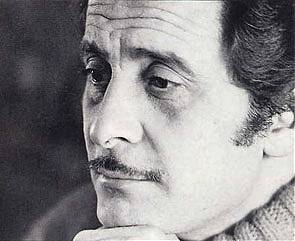

the ‘cantautori’, or singers-songwriters (who

were influenced both by the French chansonniers and

rock’n’roll: the name was suggested by a record

producer, Vincenzo Micocci) (1).

The fact that Modugno’s repertoire featured songs in dialect, although composed by the singer himself, and that Claudio Villa referred mainly to his Roman origins (he was from Rome’s neighborhood of Trastevere) complicates, but does not really interfere with the ideological implication of this confrontation, which rapidly assumed broader dimensions.

While the southern dialectal song was intoned, tenor-like, at the top of one’s voice, and was considered to be ‘conservate’, song in the Italian language - interpreted with the crooner’s or the chansonnier’s quotidian voice, and earlier on Modugno’s curious, cabaret-style drawl - was considered to be ‘innovative’. The representatives of the Neapolitan song (authors, singers, publishers, record producers) consciously sheltered behind this hostile position against ‘innovation’ increasingly making the festival of Neapolitan song (threatened by the competition of the Sanremo festival whose rules excluded songs in dialect) the sanctuary of tradition. Furthermore, they contributed decisively to the identification of Neapolitan song with the conservative past. As ‘byproducts of the dialectic’, to adapt Adorno’s useful notion to a different kind of music, always emerge; that is to say, musics and musicians eluding categorization, whose existence challenged a polarity that had already come to constitute common sense. Renato Carosone’s parodistic genius confirmed that very same dialectic, especially since it redeemed Neapolitan-ness through parody. On the other hand, the treatment reserved for E la barca tornò sola (a song in the language but modeled on the rhetorical examples of the Neapolitan tradition) could no longer allow for doubts as to whether Carosone should be listed among the ‘innovators’.

|