The ma'luf (literally, "familiar", or

"that which is customary") is the Tunisian

version of the so-called Andalusian musical tradition

believed to have originated in the Arabic speaking

communities of medieval Spain (3).

With the expulsion of the Muslims and Jews from Spain in

the wake of the Christian reconquest, their music was

transplanted into towns across North Africa where it

acquired distinctive local traits.

| When Tunisia was absorbed into

the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century, the

ma'luf was adopted by the new Turkish rulers, or

beys; in the 18th century, Muhammad al-Rashid Bey

was allegedly responsible for arranging the main

body of the repertory into thirteen vocal cycles,

or nubat, and introducing instrumental pieces

into the canon. But the ma'luf was not confined

to the aristocracy; in Tunis and other towns,

Sufi musicians sang the traditional songs both

for recreation and as a deliberate act of

preservation in their meeting places, or zwaya (s.

zawiya), in cafes and in communal festivities,

where they were enjoyed by all social classes (4). In

the same communities, Jewish musicians adapted

the melodies to Hebrew texts, both traditional

and new; the Hebrew songs, called piyyutim, were

sung in the synagogue and at home, in worship and

in family celebrations (5).

|

|

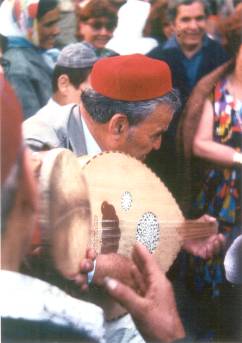

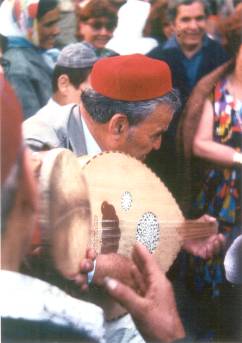

Sufi musicians

of Testour singing the ma'luf in a street

procession in a traditional wedding ritual

|

|

The ma'luf is an oral tradition,

but the song texts, in the literary Arabic genres

of muwashshah and zajal, were recorded in special

collections called safa’in (literally,

vessels). With their archaic mix of literary

Arabic and dialect, their focus, resonant of Sufi

mystic poetry, on love unfulfilled or otherwise

unattainable, and their rarefied imagery

depicting human beauty, cultivated nature,

precious jewels and the intoxicating effects of

wine, the song texts reinforce the historic

associations of the ma'luf with an idealised and

irretrievable past. For Tunisians today, the

ma'luf is symbolic of 'old Tunisia,' and of

social groups, customs and venues that are now

obsolete or otherwise transformed: the culture of

the palaces, the Sufi brotherhoods with their

marabouts and pilgrimages, the cafes with their

hashish smokers, and the Jews, artisans and

barbers who were once its principal professional

exponents. |

Jacob Bsiri,

Jewish musician of Hara Kebira, Djerba,

singing piyyutim at the annual pilgrimage to the

Ghriba synagogue |

|