| (ii) The club of Tahar and Zied Gharsa and

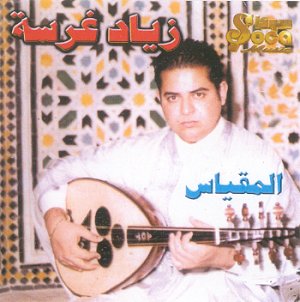

the lineage of Shaykh Khemais Tarnan For musicians and audiences alike, the undisputed bastion of authenticy for the ma'luf and its related traditions in Tunis today, is Tahar Gharsa. Born in 1933, Gharsa was a student of the Rashidiyya where he became the favoured disciple of the Rashidiyya's original chorus master, Shaykh Khemais Tarnane (d. 1966). Himself the foremost ma'luf authority of his generation, Tarnane was d'Erlanger's mentor and he played 'ud 'arbi player in the ensemble that went to Cairo; Tarnane was also the principal source of the Rashidiyya's original transcriptions and one of the ensemble's leading composers. Among connoisseurs of the ma'luf, Tahar Gharsa is considered Khemais Tarnane's 'heir.'

Gharsa's reputation for authenticity rests not so much in the actual melodic substance of his versions but rather in specific aspects of his vocal and instrumental style. These include the proper Tunisian pronunciation of individual words, the division of syllables in the Tunisian (as opposed to Egyptian) manner, nuances of vocal and instrumental articulation, and details of melodic embellishment. Exceptionally for a musician of his reputation, trained in the Rashidiyya and connected with the post-independence musical establishment, Gharsa has consistently pursued an independent career leading small solo instrumental ensembles performing traditional Tunisian songs, including the ma'luf, at private occasions such as weddings and circumcisions, and at informal venues such as cafes and hotels, eschewed as 'vulgar' by the Rashidiyya. Tahar sings solo, accompanying himself on the 'ud 'arbi. Famous for his radio recordings and live appearances, Gharsa has never made a solo commercial recording.

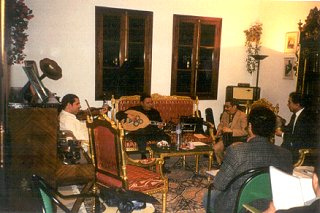

When I first met Gharsa in 1983, he told me that his mentor, Khmais Tarnane, had taught him many pieces that were unknown to the Rashidiyya and Radio ensembles. Not all were published in Al-Turath and of those that were, Tarnane's versions were different, both in their melodies and their texts. Some day, Tahar believed that he personally would have the opportunity to bring this unfamiliar repertory to light. Meanwhile, he was teaching Tarnane's versions to his youngest and most gifted son Zied, whom Tahar believed would succeed him as master of the ma'luf. In 1999, Tahar Gharsa founded a private conservatory and a club for the ma'luf with his son Zied, in a villa in El Manar, a suburb of Tunis. The club meets on Friday evenings from about 6.30 to 9.30 in its own spacious studio on the upper floor. At one end, a display of heavy mahogany furniture including a gilded red plush sofa with matching armchairs, creates a domestic rather than an institutional atmosphere; this is reinforced by a large antique record player with brass horn and photographs of legendary personalities of the ma'luf interspersed among family portraits on the walls. Tahar, playing ‘ud ‘arbi, sits on the sofa behind a low table with his ensemble of some five or six players arranged in a semicircle around him; among them is his son, Zied, playing viola. Extending towards the far end of the studio, some twenty regular participants are seated in rows of classroom chairs with folding tables; they include men and women of various ages and diverse occupations, each drawn to this particular club by their love for the ma'luf.

|

||||||||||