| Last summer I found myself in Tangier, the northern-most

Moroccan city that juts out of the African continent

towards Gibraltar and Spain, separating the Atlantic from

the Mediterranean Sea (4).

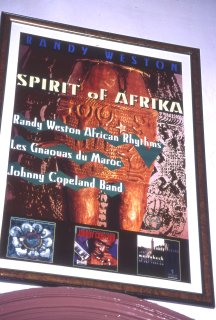

I was there to visit Abdullah El-Gourd, a master Gnawa

musician, I had met Abdullah when he was on tour in the

United States with African-American composer and pianist,

Randy Weston and his ensemble. The two of them had been

collaborating for thirty years, ever since Weston visited

Tangier for the first time in 1969, when El-Gourd was

still an electrical engineer for Voice of America radio

broadcasting, then based in Tangier. As a ma‘llem,

or spirit master, Abdullah El-Gourd is unique in that he

not only leads a ritual life in Tangier, but has an

active professional relationship with Weston, who also

lived in Tangier in the late sixties and early seventies.

While there, Weston had a music club called "African

Rhythms," frequented by people like Evelyn Waugh and

Paul and Jane Bowles, but also by Moroccan musicians and

literati. Although he left in 1975, Weston has continued

playing with the Gnawa in international venues, and with

Abdullah El-Gourd in particular. I was in Tangier to

understand how these two men, their two musical

traditions and their histories intertwined. Further, I

was interested in how both Abdullah El-Gourd and Randy

Weston, while each possessing their own relation to

slavery, music and innovation, came to be possessed by a

historical narrative that animated and defined them both.

Walking up the steep steps from the Tangier port and

entering the narrow streets of the medina, I found the

house quickly. It was indistinguishable from the others.

It wasn’t until I entered that I found the sign

designating the location. "Dar Gnawa," it said,

"Commemorating the Memory of God’s Mercy"

(dar gnawa tuhiyyu dhikra at-tarahhum) : Dar

Gnawa.

And indeed both commemoration and memory were created and displayed here. But of what and for whom? El-Gourd had transformed his traditional medina ryad into a museum of sorts, an institute for the instruction, practice and promotion of Gnawa culture. After welcoming me, Abdullah El-Gourd waved his arms in the direction of the photos on the walls, and the instruments – an electric organ, an African djembe drum, bongos, a conga drum, -- all instruments that are not found in Gnawa lilat (pl.).

"What are those?" I asked. "They’re for when we do performances," he said, using the French word spectacles, "so everyone knows what to do." Spectacles – or frajat in Arabic -- are performances done for tourists at hotels in Morocco and at festivals and concerts abroad. Lilat, on the other hand, literally "nights," are the ceremonial rituals of healing the possessed. Transforming his house into a display for the musical heritage of the Gnawa, Abdullah El-Gourd has come to possess the until-now purely oral cultural history of the Gnawa in sound, image and word, but he is also possessed by these media of documentation; they inhabit and determine him in ways that both grant and deny him agency. |

||||