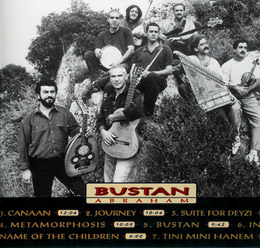

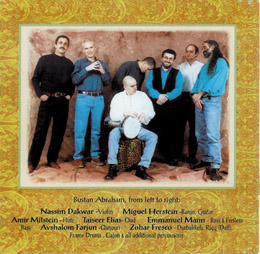

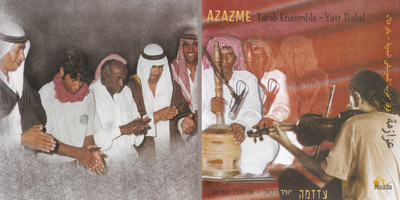

They formed a deep personal connection despite differences of class, age, gender, ethnicity, religion, and musical background. Together they created a band that merged very different musical strands, taking well-known songs in Hebrew and Arabic, but giving them a new flavor or color and, in so doing, representing the possibility for peaceful and fruitful collaboration between Jews and Arabs, Israelis and Palestinians

Nearly twenty years younger than Shoham, Jamal lives with his wife, six children, and a grandchild in a two-room, stone house, crammed among other small houses in the Muslim Quarter in the Old City. By 1990 he had grown tired of the wedding gigs that were the staple of his musical career and the incipient Palestinian uprising (Intifada), with its ban on music and celebrations, had almost completely squelched that career. It had also put a damper on his work as an actor. Jamal had plenty of contact with Israelis: he had a regular role on the pioneering Israeli television show “Neighbors,” about Jews and Arabs living in the same apartment building, and he had been teaching drumming to Jewish students at the Jerusalem Music Center (in a workshop that I directed). Jamal had also participated in a government-sponsored tour to Europe, in which he and other Palestinian musicians shared a program with Jewish musicians but did not collaborate musically. Shoham’s invitation was, in a way, the logical next step. Their first performance, a forty-five minute concert in Italy in 1990, was so well received that it led to an invitation for a return engagement at a conference of Libyan Jews to be sponsored by Qaddafi in Libya itself. As the Libyan group expected a full-length performance, Jamal and Shoham both felt that a longer program would require a full band, not just drumming. Jamal called on a number of young Palestinian musicians with whom he had performed at parties over the years. With Shoham they began to work out a mixed program of songs in Hebrew and Arabic, rehearsing far more intensively than was customary for these musicians.

The collaboration between Shoham and Jamal was not easy, tested by periods of tension and all sorts of practical obstacles, many arising from the political and military mess in which all residents of Israel and the Palestinian territories are entangled. It is a testimony to the strength of the connection that they feel and the respect that they have for each other that they managed to overcome these obstacles and create a fresh type of musical expression. The first challenge was to bridge their vastly different backgrounds.

An intuitive singer with no formal musical knowledge, Shoham had no background in Arab music prior to her work with Jamal, but was open to hearing many kinds of music. As an example she told me that she listened to Chinese opera, certainly a highly unusual choice in Israel. Shoham grew up in a Sephardic household where her Iraqi father sang and played violin, playing Jewish religious tunes on the Sabbath. Shoham characterized the tunes as a “mixture of East and West,” pointing to her father’s love of the melodies of the late American Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. Jamal, on the other hand, is an expert in Arab music with many years of experience performing hundreds of pieces in diverse settings. He has told me on numerous occasions that he is not particularly interested in other kinds of music. Nonetheless, he became deeply involved in this cross-cultural collaboration, not only teaching Shoham to sing Arabic songs but arranging the non-Arab material that Shoham proposed.

The massacre of Muslims in Hebron by a Jewish fanatic on February 25, 1994, put an end to the plans for the ground-breaking Libyan trip — this would have been the first appearance in Libya by a group from Israel. However, Alei Hazayit began to find other opportunities to perform, many of them politically charged in one way or another. One of the more important occasions was the 1994 ceremony at which representatives of the Israeli military government officially handed over control of all health services on the West Bank to the Palestinian Authority. Their audience consisted of twenty Israelis and about two hundred Palestinians. The musicians told me how tense the atmosphere was and how their mixture of songs and musical styles broke the ice by presenting a middle ground with which both sides could identify. Jamal reported that he changed the order of pieces on the spot, abandoning their plan for a formal, slowly, developing concert in order to ‘work the audience’ by foregrounding the most gripping songs. In July 1995, Alei Hazayit was the first Israeli group to perform in Jordan. Once again, the audience consisted chiefly of officials, mixed with Jordanian and Israeli business people. When Clinton visited Gaza in December 1998 the group was poised to play there, but the engagement was cancelled at the last moment. This would have been their first engagement sponsored by an official Palestinian entity. Numerous performances have been sponsored by Israeli agencies, including concerts at the President’s House, the Knesset, and in David’s Citadel in the Old City. UNESCO sponsored a concert in Ramallah, in the West Bank. In addition to these high profile occasions Alei Hazayit has also given public concerts in Israel, but, unlike the other musicians discussed below, they have not done so frequently enough to make a real name for themselves. In 1998 Jamal & Shoham led the group to their most ambitious engagement yet, the 17th Festival of Asian Arts in Hong Kong. Both of the other groups I shall discuss had performed at that festival in earlier years. While the music of Alei Hazayit was by no means the same as their predecessors’ they had clearly been selected to fill the same “world/ethnic music band from Israel” category in the festival’s roster (3).

The 1994 Hebron massacre was just one of many instances of political violence that have plagued the career of this band. Labeled as Israeli in provenance despite the preponderance of Palestinian band members, they have had invitations to Arab countries such as Libya and Morocco cancelled when the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has heated up. Because of their implicit message of peaceful coexistence and their explicit mix of Hebrew and Arabic, they were not always welcomed by all in Israel either, particularly after any bloody terrorist attack when some people are afraid to present a performance by them. In 1996, for instance, three of Alei Hazayit’s performances were canceled after a deadly bombing in the heart of Tel Aviv. Shoham felt that she was a ‘persona non grata’ for a few months and so were the Palestinian musicians in their own communities. Performing solo as a guest on someone else’s show Shoham had people shout out “not in Arabic” on at least one occasion (p.c., January 10, 1997). But after each heightening of tensions and cancellation of performances the members of the band regrouped and, in so doing, implicitly reaffirmed their commitment to their common goals.

As leaders, Shoham and Jamal have had to overcome other factors that undermine the commitment of the other musicians by threatening their economic and physical well-being. These include infrequent paying performances, hard work at frequent rehearsals, and — at times — the possible dangers involved in belonging to such an ensemble. As typical participants in Palestinian musical life these musicians were accustomed to perform with little, if any, rehearsal and to receive relatively large cash payments after each performance. They would get enough practice at these frequent performances to be able to maintain sufficient competence. But this was not possible in the new ensemble with the new repertoire. Several members of Alei Hazayit left or were asked to leave because of their reluctance to commit their time on a regular basis. A few returned when their circumstances changed or when they realized that they were missing something important.

The possible dangers of participating in this endeavor became clearest during the year-long celebration of fifty years of Israeli independence in 1998-99. Shoham was unable to accept invitations for performances that could in any way be construed as related to these celebrations because the Palestinian members of the band received threats and feared retaliation from within their community if they performed. This was brought home, for instance, when Ghidian al-Qaimari traveled to Paris to perform in a concert with a self-exiled Israeli Jew, Sara Alexander. Alexander invited him to play in Paris in a show billed as Israeli and Palestinian singers. “She’s a leftist,” Ghidian told me, “so it was fine with me.” Indeed,

Alexander touts herself as one of the first Israeli activists to speak out for an end to Israeli rule of Palestinians.

One of the differences between Arab citizens of Israel and other Palestinians is the higher level of personal danger for the latter and hence the risk involved in associating with Israeli Jews in musical performances. To date, the worst consequence of such actions for an Israeli Arab might be his reputation among certain segments of the Arab community. He has no concrete reason to fear physical harm and I am not aware of the Palestinian Authority issuing orders to Israeli Arabs concerning musical performances. Not so for Palestinians in the territories, as Ghidian’s experience with Sara Alexander proves. Ghidian was also unable to go with the group to perform in Jordan in 1995, because the Jordanians refused him entry on the basis of his having “used an enemy port” when he flew out of Israel’s Ben Gurion airport on earlier trips. And when the group was poised to perform in Gaza in early 1997 Shoham said that the Arab musicians were nervous about being seen there as collaborators (in the political sense). The Gaza trip was postponed repeatedly because of delays in signing the Hebron accord between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (p.c., January 2, 1997). In the end the trip did not take place. The Israeli government, too, limited the band’s options by refusing entry to a Palestinian musician living in Jordan whom Jamal had invited to perform with the group.

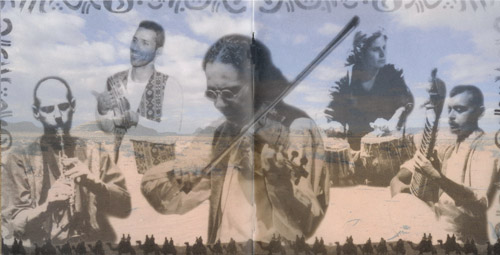

In the face of these various obstacles what is it that drew musicians to this endeavor and kept most of them there for years? There are both aesthetic and social motivations, sometimes intertwined. Jamal told me that this collaborative work provided an opportunity for him to play cleanly and delicately — as opposed to the over-amplified, aggressively competitive atmosphere at a haflah (celebration). It is also clear from his comments on the group over the years that the opportunity to shape a whole act, including repertoire, arrangements, and the singer’s presentation, was attractive to him. Others spoke about the social interaction as a welcome, integral part of their lives. I received the most explicit answers from the violinist, Omar Keinani. After complaining at length about the current situation in Arab music in Jerusalem, he said that when Jamal suggested this collaboration he thought it might be a refuge from the “boring atmosphere, this mess, that’s not music, it’s a factory.” He was referring to the Arab bands that, in his words, were only after money, turning completely materialistic after the end of the first Intifada (p.c. January 7, 1997). He did not enjoy performing anymore because the music had been cheapened by insistent dance rhythms and playing that was not on a level that he considered professional. Shoham, for her part, told me on numerous occasions that she “lives from the rhythm” of the Arab drums. There is a certain activism in such a stance as well as a business decision to carve out a niche with an unusual musical combination (4). For all of the members of this band with whom I spoke extensively over the years peaceful and productive coexistence based on mutual respect was important goal. While this was not the primary motivator for each one in joining the band, it did align well with their joint activities. |