10. Dance

|

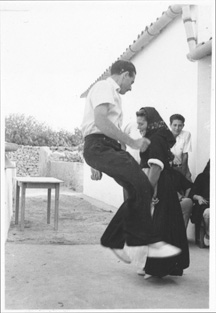

Dances traditionally took place on various occasions, including weddings; or on certain nights, in front of rural wells and fountains. There is basically one traditional dance type, which appears to be a very old form. It has two main subdivisions known as La Llarga, and La Curta, and wedding variations: ses nou rodades, ses dotze rodades, sa filera, (the nine turns, the twelve turns, the farewell). A pipe and tabor player, a castanet player and a third man playing the espasí provide the music. The male dancers, while playing the castanyoles, execute high, light-footed leaps with legs extended far up (la llarga), or lower, statelier movements (la curta), around the women, who, dressed in heavy layers of skirts and under-skirts, move in smooth, tiny steps in small circles (la curta) or wider spirals in figure

Sección Femenina of the Falange often altered costumes and dance steps in other parts of Spain, in the Pityusans they seem to have made few if any fundamental changes (Escandell 2003).

Dancers of Saint Josep, Ibiza, at the Folklore Festival and Competition. Palma de Mallorca, June 1952.

| ||||||

11. Music in the Pityusan Islands Today

|

To sum up, religious songs such as the caramelles and passos are still sometimes performed in traditional context. To a certain extent, there has been a revival and even a continuation of the redoblat and gloses, more the latter, as the redoblat technique is a difficult one and not everyone wants to learn how to do it. These genres and the musical occasions where they are traditionally performed survive more in Formentera than in Ibiza, but even in Formentera only a handful of the singers are young, and they lack the vast repertoires of the older people. Musical occasions tend to be on a formally organized level rather than the occasions traditionally set up, leading people to feel that not only has the spontaneity been lost, but that this formalizing has changed the social significance and even the actual performance structure and style of their singing. In many case, these traditions are being preserved at the cost of becoming museum and tourist objects. In June 2004, a kit of tapes and a video of oral history interviews was distributed to various town halls of thees, but systematic teaching of musical traditions, actively or passively, does not currently exist in school curricula. A small number of “folk” and folk revival groups have been formed; the best-known are Uc (Ibiza) and Aires de Formenterencs; both reinterpret some traditional music, and compose music to existing texts or new songs altogether, adding instruments and arrangements (see Joan Mari et al:19). Bands and choirs perform regularly; and there is a Conservatory, as well as an orchestra in Ibiza.Social dances take place regularly in a few centres. Since the mid-to-late 20th century, hippie colonies and individuals have introduced New Age sounds and other musics, the fledgling annual “medieval fair” includes music which is often middle eastern rather than medieval, and of course Ibiza has become known for its DJs and discotheque music, including rock compositions in ibicenco (“rock pagès”), New Age music, world music, especially from India and the Middle East, and Ibiza discothèque music, mostly house music at this time. A number of experiments in fusion are also taking place, such as Esteban Lucci’s Immaculate Ibiza (2004), which rather unconvincingly grafts occasional snippets of redoblat, flute, castanets, or espasí onto “chillout” tracks offered as a contemporary alternative to the pounding discotheque sounds. All these seem to exist in another world from what is left of traditional practice. It is almost as if, within these two small islands, Ibiza and Formentera, several musical islands existed – the newer “islands” not defined by natural sea boundaries, but by a parallel way of life which only sometimes jumps its tracks – or its currents - and influences its old island host. |