|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

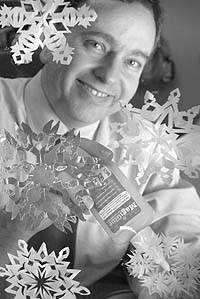

Dr. Sheldon Broedel may have a big-selling glue on his hands, but he's aiming to stick to his knitting. “We're scientists, not manufacturers,” said Broedel, majority owner and CEO of Athena Environmental Sciences Inc., a Catonsville-based company that began selling its first consumer product, MagiGlue, in December. “Glue is not really our business.” Using biotechnology as a base to solve problems and create products is what AthenaES is really about, Broedel said. The company, started in the University of Maryland, Baltimore County's business incubator program in 1994, also prides itself on its commitment to the environment. “Those principles have been in place since day one,” Broedel said. “We're mercenaries. Bring us a problem and we'll use biotechnology to fix it.” That approach went into the development of MagiGlue, now being sold in the UMBC bookstore and slated to be rolled out to other college stores as well as independent booksellers and craft shops in coming weeks. AthenaES touts MagiGlue as “an all-natural non-toxic glue composed of organic polymers, completely free of petroleum and animal by-products.” Broedel's philosophy follows very closely to that of the Green Chemistry Institute, a wing of the Washington-based American Chemical Society. Broedel has been a society member for about seven years. Institute employees work with society colleagues and others to “address global issues at the intersection of chemistry and the environment.” The group is dedicated to “the implementation of green chemistry principles into all aspects of the chemical enterprise,” according to information on its Web site. MagiGlue's unique aspect is that its stickiness can be eliminated by water. It can be used for temporary displays such as wall hangings, seasonal decorations and window displays, enabling easy dismantling and cleanup, Broedel said. Other applications include medical wound dressings and temporary machine parts assembly. The most interesting feature could become a great liability if applied in the wrong circumstances, Broedel concedes. AthenaES is working on a version resistant to water and high humidity that the company hopes to bring to market in six months to a year, he said. The company would like to assemble a MagiGlue customer base of about 250,000 before selling production rights to a medium-sized adhesive manufacturer, Broedel said. AthenaES filed for a patent in November but doesn't expect to get the official papers for years, he said. Because of its being on the market for such a short period, Broedel said he hasn't gotten back any sales figures. Nor is he making any sales forecasts at this stage. While trying to popularize MagiGlue, Broedel is giving thought to his next big idea — developing cost-effective fermentation technology that enables diesel fuel substitutes to be made without using plants. Unlike some environmentalists, Broedel pays a lot of attention to costs and financial viability. “Developing technology is important but the economics have to be there, too,” he said. The attention to economics, including the company's finances, is nothing new. “We've been profitable since day one,” Broedel says proudly. Revenue at AthenaES took a hit when the dot-com bubble burst about five years ago as customers' grant and research and development money dried up. Business has rebounded strongly with revenue growing about 20 percent per year over the past three years, Broedel said. The privately held company doesn't disclose specific revenue and profit figures. Its search for a MagiGlue partner doesn't mean AthenaES is interested in being acquired, according to Broedel. Quite the opposite. “We've turned down two [acquisition] offers,” the CEO said. “We want to remain independent.” Looking for more A 1998 “graduate” of the incubator, a government program geared toward supporting new businesses and aiding entrepreneurs, AthenaES still has its offices at the techcenter@UMBC. The company is looking to move from its 5,000-square-foot facility, occupied since 1997, to a 20,000-square-foot office elsewhere on campus. Negotiations for the new space have begun, Broedel said. “We outgrew our space some time ago,” said Broedel, whose company has 14 employees. “We'd like to stay at UMBC. We've grown up here. We hire UMBC grads. It's a great intellectual environment.” Besides starting his company there, Broedel has master's and doctorate degrees from the state college. Its alumni association named him one of five “Outstanding Alumni of the Year” last year. The 48-year-old New York native worked a stint at Martin Marietta Corp., now part of Bethesda-based defense contractor Lockheed Martin Corp., before founding AthenaES with partner Bill Jones. Jones left the company in 2001. UMBC is very interested in keeping AthenaES on campus, according to Ellen Hemmerly, executive director of the college's research and technology park. The school hopes to find additional space in the tech center before moving the company to one of three buildings planned for the college's research park, Hemmerly said. The three buildings are scheduled to open over the next three or four years, she said. “Athena is one of our most interesting companies,” said Hemmerly, who oversees the incubator, started in 1989. “They have great synergy with the university. It was started by one of our alums and we like to keep those companies around.” The company has done work for federal agencies including the Coast Guard as well as for Johns Hopkins University, Columbia University, the Mayo Clinic, and “major” pharmaceutical concerns and newer biotech firms, Broedel said. AthenaES has three divisions, with its largest being its enzyme systems group. This division makes biotech research agents and does contract research for companies working with proteins, Broedel said. Bacteria that grow in forest streams are the basis of the polymers used in MagiGlue, Broedel said. The bacteria can be used to make a range of glues, he said. The breakthrough that led to the commercialization of MagiGlue came from an unlikely source. Tiffany Broedel, the CEO's daughter, came up with a prototype during 28 days of a winter vacation last year, her father said. The younger Broedel, a criminal justice major at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania, abruptly left the scientific community shortly thereafter. “She needed a job so I gave her one,” Sheldon Broedel said. “Right after she finished she told me she didn't want to do anything like that again. Imagine what she could do if she were really interested.” The desire to do what you love runs strong in the Broedels even though individual interests differ. That drives the elder Broedel to return to the lab and leave selling MagiGlue to those more suited. “It's a good product,” he said. “But I don't want to devote my life to making it as big as Elmer's.”

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

bwtech@UMBC Incubator and Accelerator• 1450 South Rolling Road • Baltimore, MD 21227 410.455.5900 • 410.455.5901 fax • techcenter@umbc.edu |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||