2. Nostalgia, commerce and 'The Second Republic'

In more recent years, thanks to CD technology, nostalgia has

become big business. This recent vogue for 'nostalji' has

been promoted on commercial cassettes and CDs with titles which

draw attention to fact - such as, for example, 'Ud ile Nostalji',

'Kanun ile Nostalji' ('Nostalgia with Ud', etc.). Live

performance has followed.

Cover of Rusen Yilmaz's 'Ud ile

Nostalji' (c. 1994)

|

|

'Unutturamaz Seni Hic

Bir Sey' 'Unutturamaz

Seni Hic Bir Sey' ('Nothing will make me forget

you'), by Ekrem Guyer. Ekrem Guyer was born in Izmir

in 1921 and spent his working life as a light classical

singer at the Ankara Radio station. He died in 1954: his

most famous compositions were composed in the 1940s and

50s. The example here is performed by Rusen Yilmaz at the

ud (short-necked lute), on a cassette entitled 'Ud ile

Nostalji', the other songs from which largely come from

the 1940s and 50s. A brief taksim improvisation ends, and

the piece begins. The intimate style is closely connected

with a more popular style of nostalgia, and contrasts

markedly with the examples of 'official nostalgia' (see

below).

|

from

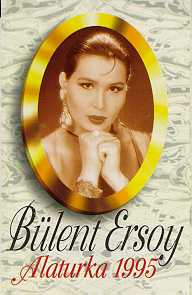

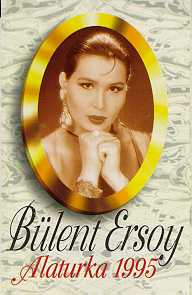

'Alaturka 1995' from

'Alaturka 1995' Bulent

Ersoy released a cassette entitled 'Alaturka 1995', in a

resolutely 'classical' style. It began with a reworking

of Munir Nureddin Selcuk's famous 'Aziz Istanbul', a

somewhat nostalgic view of the city from Camlica, a hill

on the Asian side. Where Munir Nureddin hinted at the

sound of the call to prayer that he imagines coming from

the mosques below him, Bulent Ersoy makes this reference

explicit, singing the call to prayer herself. This caused

outrage in many quarters, since Bulent is a transsexual.

The cassette was, nonetheless, a popular hit.

|

|

|

Cover of Bulent

Ersoy's Alaturka 1995.

The restrained 'classical' pose marks a somewhat

humourous departure from the erotic poses that she

strikes on other cassette covers. |

Advertisements in papers invite the reader to participate in

'an evening of nostalgia' at such-and-such a gazino (music club).

In fact, my kanun teacher regularly performed in such

clubs.

|

My kanun teacher and

friends |

|

|

| My

kanun teacher

and friends (ud, yayli tanbur, def and singer); halfway

through a Nihavent Fasli. All musicians are seated, and

the voice is simply one of an integrated group. |

The French term appropriated by Turks, 'nostalji',

reveals the connection between a certain culturally sanctioned

form of memory and a modernist nationalism which sought quite

explicitly to forget its past. New sound recording technology

(particularly connected with CDs and the digital 'remastering' of

old recordings) has made possible new forms of historical

consciousness, marketed as 'nostalgia'. But this is not merely a

product of a consumer capitalism which turns to the past in

search of novelty. In other senses nostalgia might be interpreted

as a change in popular historical consciousness that accompanies

wider social processes. In particular, I would argue, one should

connect the vogue for nostalgia with a sense of failure

(experienced in a variety of contexts) of the nationalist reform

project. This is a sense of failure that is cast in a temporal

idiom (of 'winding back the clock') precisely because the telos

of Kemalist nationalism has been so resolute, so determined that

no backward glance could ever be permitted. Under threat from the

emerging global economic and political forces that problematise

traditional territorially conceived nationalisms, and, more

specifically, from Islamist resurgence, one might describe

Kemalism as being in a state of nervous retreat. Demands for the

institution of the seriat (Kuranic law) grow increasingly

stronger, and Islamist thinking dominates the local elections

across Turkey (3). A 'Second

Republic' has recently been discussed, in attempts to close the

door on many aspects of Kemalist reformism.

This sense of retreat stems from what is now seen in many

quarters as an inability to live up to the Kemalist legacy, and a

quiet recognition that an ideology which demanded that the past

should be forgotten was untenable.

|

Official

nostalgia Official

nostalgia The song is a recording of Tatyos

Efendi's 'Cesm-i Celladin ne Kanlar Doktu Kagithane'de'.

Tatyos Efendi was born in Istanbul in 1855 and died in

1913. The song describes the bitter-sweet torments

suffered by lovers in Kagithane, then a popular excursion

spot, now a slum disrict by the side of the Golden Horn.

The City Council sponsored and released this recording in

1995; the style is close to that of the TRT, with a large

unison orchestra and chorus.

|

| Cover

of Istanbul Sarkilari II, from which the Tatyos Efendi

piece in music example 3 is taken. An orientalist vision

of Istanbul dominates the cover. The English subtitle

indicates both the 'official' nature of the production,

and the fact that it is being marketed for an outside

audience. |

Many Turks today portray the Ottoman past as a moment of

imperial glory when Turks dominated the world stage; a world in

which the various millet (religious minorities) of the

Ottoman empire participated as equals in an East Mediterranean

linguistic, literary, architectural, dietary, and, of course,

musical culture. Sporadic moves against religious minority

communities on the part of the state, and resurgent Islamism in

recent years has often made life for those Armenians, Jews and

Greeks who chose to return to Turkey after 1923 difficult. This

is a bitter pill to swallow for Kemalists: those who still adhere

to Kemalism as a political creed speak (privately) of their

feelings that the process of reform was, perhaps, too quick, too

forceful, and insufficiently attentive to issues of human rights

to succeed in its goals.

The music which represents this golden past, existing, as

music does, in the domain of time and memory, expresses precisely

this complex, gloomy ambivalence for many Kemalists. This is a

music which has, as it were, been made available for nostalgia by

the fact that its history has been denied, or rather, coopted.

This has not been difficult. In a world in which very few people

can read Ottoman script, and cannot master the interpretative

skills to make sense of the few Ottoman musical texts that do

exist, historical research of any kind is impossible for the

majority of Turkish art music practicioners. Historical writing

also implies (or even demands) a sense of critical continuity

which has been politically impossible. For these reasons, Turkish

art music signifies the past, but is constantly presented in ways

that prohibit its reengagement with the present or possible

futures. This process is worth exploring in a little more detail,

since, as a form of historical policing, it is fraught with

problems. When the whole basis of social and cultural order is

based on the premise that the past is irrelevant, or rather, only

relevant in as much as it has been surpassed, how can the past be

materially presented and ideologically controlled in ways which

limit its always subversive implications? This problem is not, of

course, limited to modern Turkey.

Forward | Back | Stokes main

page | References