|

In a country where the sea is thronged with islands, it may seem strange that the music of the Aegean islands, particularly the Cyclades, Sporades, Dodecanese, and Saronic Gulf Islands, should be called nisiotika (island songs). After all, Crete is an island, Lesvos, Cyprus and the Ionian islands are islands, and yet their songs are not referred to as nisiotika. All Greek island music is influenced by its specific geographical location and by a history of occupation by foreign forces as well as constant raids by marauding pirates of various nationalities: Saracen, Tunisian, Italian and even Peloponnesian Greeks from Mani. The islands also formed a porous border area where the persecuted could flee in difficult times.

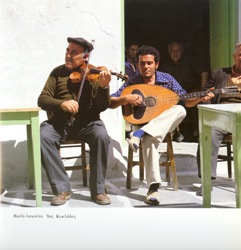

Throughout Greece, music is either played by a small ensemble of instrumentalists, or by a pair of musicians, one taking the lead on a wind instrument (clarinet or folk oboe, violin, rebec or bagpipe), the other accompanying on a drum or lute). In Crete, the pair is a lyra, or small rebec that plays the melodic line and improvises on it, and laouto, a folk lute, used as a rhythmic and sometimes harmonic accompaniment. For the nisiotika, the combination is usually violin and laouto. The dance rhythms and songs associated with these instruments may be particular to a single island, but the group of islands may also have an overall character. This is true, for example, of the Cyclades, twenty-four of which are inhabited. The music of the Cyclades is usually in one of two dance rhythms, the syrtos or the ballos, the former being a circle or line dance, the latter, a couple dance probably dating from the Frankish occupation of the islands in the 13th to 16th centuries. Unlike the songs of mainland Greece, characterized by unrhymed 15-syllable verse, the songs of the islands are often in rhymed distichs, usually, but not always, of 15 syllables. On many islands, skilled singers of these pairs of rhymed lines, or mantinadhes engage in competitions in which they improvise lyrics, usually at each other’s expense. The competitive element in the mantinadhes may have been what kept the tradition alive, especially in Crete, where, as Herzfeld [1] and others have amply demonstrated, the mantinadha, like the dance, was a measure of masculine pride. |