|

That songs like “Thalassaki mou” are pleasing melodies and dances can be understood by the causal listener, but their poetry needs a more careful ear. Musicians, especially those who perform early music, are familiar is the technique of melisma. Technically the term, derived from the ancient Greek word for melody, means a group of notes sung to a single syllable. It was first applied in Byzantine times to the spiritual or so-called jubilant songs, often consisting of the single word alliluiah , which were characterized by their highly embellished style. Both Saint Paul and Saint Augustine refer to these songs. Augustine says “He who jubilates sings no words: it is a song of joy without words [4].” Such improvisation was regarded as an expression of ecstasy. In later Greek music, as in the Byzantine and late Ottoman music it was derived from, a type of vocal improvisation developed based on a simple couplet of verse. It was known as gazel in Turkish, and amané in Greek. The singer would demonstrate not only his or her virtuosity by improvising on a particular musical mode, but would elaborate the melodic line with elaborate melisma or ornamentation. I would like to extend the concept of melisma from its usual, strictly musical sense, to the lyrics of the songs, that is, to the poetry. We are all familiar with the poetic techniques that cause us to dwell on key words and phrases. In the Hebrew Bible, and in the folk songs and poetry of many countries, repetition, in the form of parallel half-lines of poetry, is a common technique of emphasis, but we often misunderstand the elaboration of phrases as simple repetition. According to the Biblical scholar Robert Alter, “literary thought abhors complete parallelism, just as language resists true synonimity, always introducing small wedges of difference between closely akin terms” [5].The folk poets of Greece were no exception. So as to make the techniques of parallelism in island songs clearer I have provided a transliteration of the Greek lyrics:

There is very obvious use of melismatic repetition in this opening stanza and its emotional shifts are quite surprising. If we remove some of the repetition from the opening stanza we end up with a pair of lines in the standard 15-syllable meter of Greek folk song. And if we translate this literally, we arrive at something like this: Sea, the sea-farers (my little sea), do not sea-scourge them. we have been sea-squandered by you; because of you we stay awake all night. Although it is popular throughout the Aegean, the song is thought to have originated in Kalymnos (Baud Bovy recorded a version of it there in the 1930’s [6]), an island where most of the male population was engaged, until recently, in the dangerous occupation of sponge-diving. To the Kalymniots, as to the inhabitants of most small Aegean islands, the sea was all things: life-giver, death-bringer, crippler, depriver, food, poison, enemy, lover. The sea, in this song, is addressed by women who wait, sleepless, for their husbands, sons, brothers, to return from the long months aboard small boats, sleeping in shifts, and risking their lives daily. The lilting rhythm of the kalamatianos may lull the listener into thinking the song is lighthearted, but there is nothing soothing in the lyrics, which take the form of a prayer to a powerful god, capricious as a child, who rules over every aspect of island life. Nor should we be fooled by the tender address thalassaki mou (my little sea) interpolated into the metrical form. This is the prayer of a mother asking the sea to have mercy on her son, and if sweet words will advance her cause, she must use them. This opening stanza of the Thalassaki might be described as a couplet that has been ornamented by repetition for heightened emotional effect, but as in the poetry of the Bible, there is more going on than mere repetition. The word thalassa (sea) is not simply repeated but stretched into compounds, one of them unusual (thalassonoume), the other a hapax (thalasoderneis), intensifying the passionate address. By the end of the first stanza, our ears are drenched in the sound of the sea, and we are in awe of its power. This sort of intensified repetition is not the only melismatic, device employed in the song. The refrain itself underlines, at the end of each verse, the speaker’s ambivalence towards the sea which is all things to her. It also gives the listener a point of repose: Thalassa ki’almiro nero, na se xehaso den boro. Sea and salt water, I can’t forget you. In the verse that follows, the sea is asked to become rose-water to sprinkle on the door. The verse ends with a line that will become the final line of all the remaining stanzas “and bring back my little bird (a common epithet for a child) to me.” In the third stanza, the sea is addressed again, this time as the one who drowned the husband of a young girl. The sea is told, in the final stanza, that the girl is young and that black clothes (i.e. the traditional mourning clothes) do not become her (den tis pan ta mavra). In all three verses we find the use of another type of intensifier: the interpolation of the exclamation “Och Aman!” – the Greek equivalent of “Woe is me!” or “Alas!” Such extra musical phrases, called tsakismata are common in Greek folk song, and also heighten the emotional impact of the line. Here is the first line of the second stanza as it would appear in 15 syllable verse:

And here it is as it appears in the song: Thalassa, thalassa pou ton epnixes, (och, och aman!) tis kopelas ton andra. The tsakisma has been fitted to the melodic and rhythmic line so that it appears to be only a semantic interpolation. Subliminally, at least, it is also a metrical interpolation in the original 15 syllable line. So although there is no musical melisma at work here, you have something that operates in the same way as a melisma: a textual ornament that heightens the drama.

In terms of poetic technique, Stopa kai sto xanaleo is a simpler song than Thalassaki, but the combination of dialogue with the prayer of the sailor for his magical transformation into a boat is both dramatic and comforting. Here, the long melodic melismata (the word xanaleo is stretched over fifteen pitches) at the end of the first hemistiches of each verse serve to heighten the emotional effect of the song. Tzivaeri is also poetically simpler than Thalassaki. Again, the song is claimed by the natives of Kalymnos as their own, but versions of it are sung on many islands, and it is impossible to

It is possible, even without understanding the language not to recognize the musical melismata on the word Tzivaeri. What is overwhelming in this song, however, is the repetition of the refrain, with its variation: sigana sigana sigana kai tapeina/sigana sigana, sigana pato sti yi -- words of resignation, self-recrimination, and sorrow beyond measure.

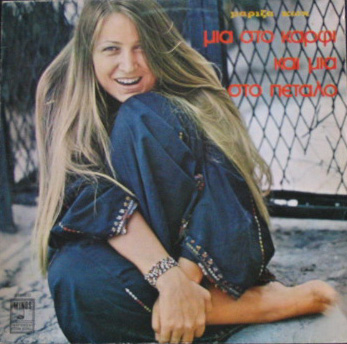

Indeed these island songs are among the most emotionally affecting songs in the Greek repertoire and yet they have received less attention from Greek and foreign musicologists and folklorists than the songs of Epirus, Thrace or Macedonia. Is it because their lilting melodies and rhythms made them sound, superficially, light-hearted? Or is it because the tradition of live performance has been lost on so many islands? The cheapening of them by “skyladhika” (doggy) performers, including those of the family of Eirini Konitopoulou-Legaki, and by Yiannis Parios occurred in the eighties and nineties, but it has been counterbalanced by more serious Greek singers like Koch, Savina Yianatou and Maria Farandouri. In 2004, Koch released a new CD of island songs called

A Breath of the Aegean. Her chief musician on the recording, and perhaps the best living exponent of the

nisiotiko violi

(island violin) Nikos Economides. Economides, despite his remarkable

virtuosity,

remains within the bounds of tradition. A native of Chios, he travelled all over the Aegean in his youth, collecting tunes as he played with old violinists who were still performing at weddings and festivals. His solos on the CD

A Breath of the Aegean are remarkable, and Koch’s voice is as fine as ever in one of the best-loved Aegean songs, probably from the Dodecanese:

(mp3

file))

Mes sto Aigaio ta nera. In the Waters of the Aegean

From the CD Mariza Koch: Pnoi tou Aigaou (Mariza Koch: A Breath of the Aegean).

Mes stou Aigaiou, (provale na deis) mes

stou Aigaiou ta nera, o…mes stou Aigaiou ta nera, angeli

fterougizoun

Kai mesa sto fter…(voitha Panaghia)

kai mes’sto fterougisma tous, o… kai mesa sto fterougisma

tous, triantafylla skorpizoun.

Aigaio mou ga…, (voitha Panagia) na galinepse

o… na

galinepse ta galana nera sou.

Na erthoun ta, (voitha Panaghia), na erthoun ta, o…na

erthoun ta paidhakia sou sta foteina nisia sou.

In the waters of the

Aegean (come out and see), in the waters of the Aegean, oh…

in the waters of the Aegean angels are flying

And as they fl… (Help,

Virgin!) and as they fly, oh….and as they fly they scatter

roses.

Aegean ca…(Help Virgin!),

Aegean calm, oh….Aegean calm your blue waters

So your chil… (Help

Virgin) so your children, oh….so your children can come to

your shining islands

Again the song makes use of repeated phrases and half lines, with the words broken in two and completed in repetition, as well as the

tsakismata (interpolations) typical of Greek folk verse. And again, the sea is addressed directly as a deity, its power accentuated by the interpolated appeals to the Virgin. Koch has maintained the traditional instrumentation for these songs but the she takes liberties with rhythm and ornamentation that are a mark of her individual performance style.

The popularity of nisiotika owes much to artists like Konitopoulou, and more recently to Koch and Economides, both of whom live and work in Athens. Without their revivals and recordings, it is doubtful if many of the

nisiotika would be familiar to Greeks, especially the younger audiences. Anyone hoping to find live music on the Cyclades, the Islands of the Saronic Gulf, or the even the Dodecanese is more likely to hear imported than local music. A handful of the better-known

nisiotika have, however, become part of the pan-Greek musical repertoire. They deserve to have a place beside the more dramatic music of Epirus, Thrace, Roumeli and Crete. Musically and poetically they bear comparison with the finest examples of Greek folk song. |