Before I expand my own analytical narrative about the Jewish Mediterranean, it is necessary to establish a deeper level of gender in Jewish sacred and religious practice, the level occupied by the shechinah, the feminine sacred. The shechinah, literally defined as "the Divine Presence of God," possesses specific archetypal characteristics, or sefirot in Hebrew. Sefirot provide images or representations of God, theologically enabling one to think about God and the manifold ways in which God is present in human life, but without giving God a specific, iconic form (see, e.g., Wolfson 1992). Sefirot do not function by multiplying the meanings or interpretations of God, but rather by intensifying them. The shechinah exists primarily as metaphor, as the Sabbath bride who arrives in the Jewish community at the beginning of the Sabbath on Friday night and whose presence embodies the union of the Jewish community during the course of the Sabbath. The ritual of the synagogue service that opens the Sabbath employs the shechinah as a root metaphor for union itself. With ritual and song the men praying in the synagogue welcome the Sabbath bride, turning toward the back of the synagogue at a specific moment in ritual and escorting her with their songs, notably with "L’cha dodi," to the front of the synagogue, where they themselves gather at the moments of most intense prayer before the Torah, or the five Books of Moses (see Cornbleet 1994). Though ritual and music physically acknowledge the arrival of the shechinah—the congregation as a whole turns and seems to greet an invisible presence—they do not necessarily think about a feminization of the synagogue’s ritual space as engage in a performance of community. Ritual performance intensifies meaning, without necessarily specifying it. The Sabbath is the moment in the week when the sense of Jewish community is most intensive, and it is noteworthy that it is the moment in which gender distinctions and the musical expression of these distinctions are most extreme, in both the home and the synagogue. Prayer in the synagogue is not relegated only to the Sabbath, but in fact is a daily component of community life. During the week, however, the shechinah occupies a ritual space outside the community; indeed, the shechinah lives in exile during the week, an exile that itself possesses the additional metonymic meaning of representing diaspora. The Friday Sabbath rituals in the synagogue only highlight this outsider status during the week. First of all, the shechinah must enter the synagogue from the outside the sanctuary and the building of the synagogue itself. In so doing, she enters into a space that has, during the week and literally at the moment of her entrance, been occupied exclusively by men according to orthodox principles. During her entrance the shechinah comes from the West and moves toward the East, for the Jewish synagogue is oriented toward the East, toward mizrakh, toward Jerusalem and the in-gathering after diaspora. We witness, then, a much larger historical significance for the ritual of the shechinah’s arrival and transformation of masculine ritual space into feminine sacred and narrative space.

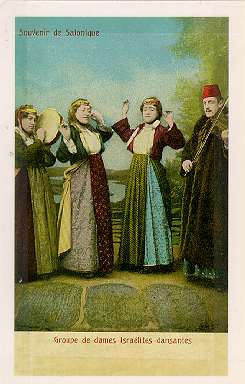

The arrival of the Sabbath bride has sweeping metonymic significance, for she gives meaning to the community itself and to its sustenance over time. Her arrival is the moment of hopefulness, of the reimagination of Jewish history in the land of Israel. Necessarily, which is to say, because of the different histories of the many Jewish communities of the diaspora, this reimagination assumes many forms. In traditional interpretations, the shechinah also occupies a metaphoric domain connected to rituals of reproduction. Her arrival and departure—and by extension her demarcation of domains of selfness and otherness—are ritually performed in the wedding ceremony. The shechinah, in this sense, further accrues the symbolic meanings of selfness through the community’s in-gathering in the home, synagogue, and wedding, many of them iconographically represented on the postcards in Example 3, which were printed in early twentieth-century centers of Jewish Mediterranean culture, Greece, Bosnia, and Tunisia (cf. Avishur 1990).

Postcards with representations of women in Mediterranean Jewish culture, early 20th century It is extremely significant that the symbolism of the shechinah is that of the wedding, which therefore ritualizes the arrival of the Sabbath bride in preparation for union with the masculine sacred in the space and time of the synagogue. The Sabbath, beginning on Friday night at sunset and ending on Saturday night, also at sunset, is rich with these metaphors of wedding, union, and the reproduction of the community. The Sabbath, thus, is temporally and physically the space in-between, a time of ending and beginning, of arrival and departure, of celebrating the Self as distinct from the Other. The music of the Sabbath, both in the synagogue and in the home, celebrates and ritualizes the union in these spaces cohabited by the feminine sacred and the masculine sacred. Example 5 is the performance of an eighteenth-century work composed for a wedding in the northern Italian city of Mantua, which was one of the most important early modern centers of Jewish music and culture.

Le-mi ekhpots la’asot yeqar (To Whom Should I Give Honor) [The text’s author is unknown] To whom should I give honor? Surely to those souls who enter into union in the way of a man with a woman. In the treasure-house where God shapes the soul, its stronghold is already marked out for its future mate. Life be his desire, she will be his helpmate. Let them never be opposed, never know tumult. Though a man’s wealth be great, he should sell all his possessions to take unto himself a daughter of wisdom. Thus shall he greatly inherit the honor of the Torah ways. Who would destroy this by covetousness? This wise woman will share his bread. Protected as his own ewe lamb, she is silent, though shearers come. He will come to honor her more than himself. Sheltered under his wing, she will be lifted up high over his house. Nations will look upon their glory all their days. Their union will be perfect, they will avoid malice. The longing of a woman is to her husband who shapes her as from a void. Yet, though he is her "lord," he shows her abounding love. She builds her house in joy, without strife or contention. O thou Almighty God, grant our beloved friends blessings unbounded forever, yes, through eternity! [Translation adapted by the author from M. Feist] Concepts of the feminine sacred contrast with those of the masculine sacred, and these take metaphoric form, for example, on the Sabbath with the welcoming of the Sabbath bride in different ways into the home, a feminized space, and into the synagogue, a masculinized space. The ritualized arrivals of the feminine sacred draw attention to and ritualize the liminal spaces between secular and sacred worlds. The shechinah also draws attention to the distinctions between Self and Other, for God’s feminine presence resides normally in exile, and among the historical conditions for which she serves as a metaphor is Jewish diaspora itself. If we think of the sacred as having two genders, then, the model of selfness—rituals of reproduction, where all is timeless and placeless—seems to collapse. In this article, however, I concern myself with the ways in which (1) the shechinah actually confirms the conditions of otherness, and (2) the Sabbath bride further comes to represent the historical condition of exile and diaspora, and the ways they dialectically map Jewish history on the Mediterranean. |