| A musical performance is related to a series of

socio-musical (if not also extra-musical) processes that

not only can influence the growth of the music being

performed but can even determine the same performance

intrinsically. To give a simple example, one can say that

the way in which a singer performs his song and the

audience perceives it depends, among other things, on the

practical and theoretical musical training of the singer;

his psycho-physical state at the moment of the

performance; his popularity with the audience; the

musical and textual structure of the song; the feedback

of the audience; comparisons of the present audience with

past interpretations either of the same singer or of

other singers; if not also on the general acoustics of

the place, the latter being the result of a social

decision rather than an arbitrary one. All this may urge

the singer, for example, to give importance to certain

words rather than others; or in the case of improvised

music such as jazz, to repeat certain motives that s/he

thinks had been well received by either the present

audience or past audiences. In this quite complex

framework a series of socio-musical processes amalgamated

with, or imposed on, other processes and factors which in

themselves might seem to be 'purely' musical would

emerge. One of the ways in which one can identify some of

these processes present in a musical performance, such as

that of the spirtu pront, is through the

ethnography of musical performance. The events which I

describe here present two quite contrasting spirtu

pront sessions: the first in a bar at Zejtun in which

the context is very familiar for both the audience and

the ghannejja, while the second session took place

in a more formal public context on Imnarja eve. At

first, the following accounts will avoid academic

rhetoric in order to get the reader closer to the world

from which the elicited musical examples have

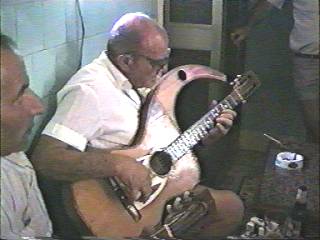

originated. a. A spirtu pront session in a bar at Zejtun on Sunday morning. The bar was crowded with men drinking beer, eating appetisers, chatting and listening to sessions of the spirtu pront. The place was quite noisy if one was trying to follow the ongoing sessions. This has occasionally urged certain participating ghannejja to ask those drinking by the bar to lower their voices. Some of those present preferred to sit by the bar, more interested in having a word with their friends rather than following the sessions. Others could be seen seated on low stools, drinking while following the sessions. The participating ghannejja were standing in the inner part of the bar. The number of ghannejja who wished to participate in one session or another was quite great so much that the sessions were composed of six ghannejja. The sessions took place one after the other with a short break of seven minutes or so in-between each session. During these intervals the guitarists had the opportunity to drink something, exchange a word with those present and release their fingers from the continuous pressure of the strings. The only two women present in the bar were members of the owner's family who were giving a helping hand in the serving of drinks.

The session, which the present study will focus on, started at about twenty past eleven. After an agreement among the present ghannejja about who would be participating, the lead guitarist accompanied by the other two guitarists began playing a popular folk tune in waltz tempo so as to announce the beginning of another session. Till then the ghannejja had taken their standing position and ordered some fizzy drinks to drink during the one-hour session. Their age ranged from twenty-six to forty-six. The youngest one sung his first ghanja in a standing position but then he sat for the remaining session (singing in a sitting position is a very uncommon practice in ghana). Between one session and another the ghannejja took a sip of their drinks which were laid down for them on tables. Their singing was quite loud for the small place they were singing in, but as Lortat-Jacob (1995: 2) has noticed: "In Mediterranean countries things seem to acquire a reality when they are debated out loud".

During the session I was able to observe that the guitar improvisations played in between the stanzas were being almost ignored by the present audience. All this was demonstrated through the movement that took place as soon as the lead guitarist started improvising, varying from the barman serving appetisers and drinks, to members of the audience crossing the bar.

This lack of importance accorded to the instrumental interludes was confirmed by an incident in which I was involved while preparing my video camera to film the session. While preparing my camera I realized that I had to change the videotape in the middle of the session (16). One member of the audience, on noticing that I was engaged in this task, suggested to the lead guitarist that he extend one of his interludes to double the length in order for me to have enough time to change the tape without, as he put it, "missing any ghanja". The first example shows a normal qalba (or interlude) composed of eight measures extracted from the same session under investigation. One can compare ex. 1 to ex. 2; the latter consisting of the extended qalba made up of sixteen measures.

At this stage it is worth mentioning the fact that during the performance this same ghana dilettante has insisted that I shouldn't move my camera away from the ghannej who happened to be in the process of putting his ghanja together. According to him I could only do this during the improvisations of the lead guitarist. The listeners present also had their part in the formation of some of the kadenzi (the plural of kadenza) which took place in the third section of the session. At this point it is worth remembering that the longer the kadenza the more the bravura of the ghannej will be. Some encouragement from those present may motivate the ghannej to extend his kadenza to one of more than two quatrains. The third example demonstrates a kadenza of two quatrains sung by the youngest of the participating ghannejja. Due to his young age this ghannej had not yet cultivated an entourage big enough to give him the necessary support for an extended kadenza. At that particular moment the support seemed to be as important as the inspiration itself. Ex. 4 is an example of a kadenza of three quatrains performed by one of the ghannejja who was encouraged to do so by a fellow ghannej who was taking part in the same session. Ex. 5 includes the kadenza of the ghannej who brought the session to its end.

.

This example includes a kadenza

of four quatrains motivated by two factors: the

encouragement by a member of the audience who has indexed

the number three with his fingers for this ghannej

to extend the kadenza to three quatrains; and the

necessity that the last ghannej felt to give a

'grand finale' to the session. The encouragement given to

him has motivated him to stretch his kadenza to

four quatrains, more than expected from him. In such a

small place as the bar in question both the aspirations

of the audience and the various kinds of friendships were

in their natural context and could easily be negotiated

and transformed. b. The spirtu pront on Imnarja eve (1995) I arrived at Buskett at about 9 p.m. The place was so crowded with Maltese and foreigners that it was almost impossible to move. The atmosphere was typically Maltese on Imnarja eve: some families were sitting under the Greenwood trees ready to have their meals. Others were ready from their meal and were lying on the ground. The youths that were next to the vendors of fast foods were almost blocking the narrow passages of the garden. Others were visiting the Agricultural Show organised by the Maltese Agrarian Society. With no small effort I succeeded in getting close to a stage on which a show of local artistic talent was in progress. The programme included, among other things, Maltese folk dancing, wind-band playing, Maltese pop song singing and two spirtu pront sessions. The first session began at around 11 p.m. whilst the second group of ghannejja appeared on stage at about midnight (for the purpose of the present study only the first session has been considered). The sessions were of half-an-hour each with a different item in between; as if the organisers were aware of the fact that an-hour-long spirtu pront session could have been too much for certain members of the audience unfamiliar with this style of singing. As soon as the ghannejja and guitarists went on stage, they were introduced one by one to the audience by the evening's compaire. He introduced them by both their names and nicknames. In the context of ghana, the nickname is of important significance because it contributes considerably to the identity formation of a ghannej. The components of such identity vary: from the character quality of the ghannej himself to his popularity with the general public and from his superb ability to rhyme his quatrains to his often used melodic motive from one session to another; from his vocal timbre to his life story and the many experiences that he has had as a result of emigration. From the MC's interview with the ghannejja I could sense a feeling of nervousness from their trembling voices. And this is understandable! The context was quite formal for them: on a stage, with a microphone in their hands, with the strong lights of the spotlights directed in their eyes and above all performing in the presence of a mixed audience with various expectations if not also outsiders to the world of ghana. In bars things take a different shape: the audience sits close to the performers; the bar is relatively a small place in which the loud singing is more a means of persuasion rather than an acoustic exigency and above all the bar as an environment is less formal as is evident by the liberties the ghannejja take in drinking between one quatrain and another. All this was missing from the session at Buskett.

As soon as the first ghannej started singing, the reaction of the audience was quite mixed. Some applauded as soon as this same ghannej finished-off his first ghanja. Others, who were very close to the stage, walked away to avoid the loud volume that was coming out of the speakers, caused by an inappropriate use of the microphone by the same ghannejja. Other members of the audience, especially the women, continued with their chatting as if nothing was happening on stage. I took the impression that these remained there for honoring another relic of the past rather than to listen to ghana. For these, the nostalgia that ghana brings with it on Imnarja eve was more important than the same ghana. As Blacking puts it: "people's interest may be less in the music itself than in its associated social activities" (1973: 43). The ghannejja did their best to minimize the pressures that normally accompany such a context. For instance, one of them lit up a cigarette as soon as he finished singing his first ghanja. Other ghannejja tried to minimize, however superficially, their detachment from the public by waving their hands at some members of the audience. More than that, one of the ghannejja felt that he would be doing nothing wrong if he exchanges a word with the lead guitarist while the latter was improvising his qalba. The lead guitarist continued with his improvisation while at the same time talked to the same ghannnej. Both the ghannej and the guitarist were aware of the fact that the majority of the audience not actively involved what was happening on stage. All this dovetails neatly with Blacking's assertion that "musicians know that it is possible to get away with a bad or inaccurate performance with an audience that looks but does not listen" (1973: 10). Ex. 6: A complete qalba from Buskett Ex. 6 shows a qalba derived from the session at Buskett. One can notice a more rhythmically coherent and dense musical structure when comparing this qalba to the one transcribed in ex. 7. The latter includes a transcription of the improvisation as played by the lead guitarist while he was chatting with the ghannej. Ex. 7 also indicates a particular moment (in rectangular frame) of interruption in the melodic of the lead guitarist caused by the situation already described. I got the impression that the effort that was being done to create a more informal atmosphere was more important than the musical material that was being presented that evening; as if the only imposition accepted by the ghannejja was that of the spirtu pront style itself.

|