| The history of the Gnawa is largely oral. Apart from

a few books in French, there is hardly any scholarship on

the Gnawa at all. Even the slave records from that time

period are difficult to access. Unlike other Sufi-influenced

groups in Morocco – like the Aissawa, for example (see

Dermenghem 1954), or the Hamadsha (see Crapanzano 1973)

– there is no shaykh who has left writings,

not even any oral hagiography that is passed on from

generation to generation. The transmission of Gnawa

culture has been in the gestures, movements and attitudes

of the body possessed. And in the musical and aesthetic

repertoire, of course. The history is in the songs –

all 243 of them. But even the songs themselves do not

recount stories. There is no narrative line in the

lyrics, only invocations to the different saints and

spirits recognized by the Gnawa – Sidi Bilal,

Abdulqadr Jilani, Sidi Musa, Lalla Aisha, Si Buhali,

others. The names of these mluk (or possessors) are

repeated over and over, their qualities praised, their

aid solicited. The spirits of the ancestors are still

alive. Why then would they need to be conjured in books

when their presence is conjured regularly in the bodies

of the entranced, the majdubin? As philosopher Edward

Casey notes (1987), the body remembers the past as a form

of presence. Body memory experiences the past as co-immanent

with the present. By dancing to the spirits, moving to

their dictates and rhythms (as Barbara Browning

demonstrates in her 1995 book on samba), history is

embodied and made to live in the present. In part, the absence of any written history protects the Gnawa from criticism from other Moroccans, as the syncretic beliefs of the Gnawa, expressed in a system of African aesthetics, are less than what most consider to be mainstream Islam in Morocco. Indeed, of all the mystic cults in Morocco that employ trance as a way of communing with the spiritual world, the Gnawa are the least understood. They are often compared to black magicians – that is, they are accused of practicing black magic and are also the targets of racism. "The Slaves of God," as anthropologist Viviana Pacques calls the Gnawa (1991), have reason to be circumspect about their manner of practicing devotion. Although the masters of a generation or two ago are still remembered in conversation, they are not reified. The pantheon of spirits is not represented in any of the images displayed in Dar Gnawa. Moroccans do not portray the spirits in images except as they incarnate in the bodies of the believers. In the Gnawa worldview, the spirits are all around us, sometimes taking fleshly form, sometimes not. The images we do see on the wall in Dar Gnawa, however, are somewhat surprising. Abdullah El-Gourd refers to them as the "ancestors": Ha huma an-nass al-qdam, there are the ancestors, the m’allam remarked when I approached the photographs to read the inscriptions in small print on the bottom. There were pictures of Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Eric Dolphy, Dexter Gordon, Thelonius Monk, Milt Hinton, Roy Eldridge, Johnny Copeland, Ben Webster, Archie Shepp, and, of course, Randy Weston, who is surrounded by pictures of the Gnawa masters. How is it that African-Americans jazz legends come to

define the ancestors in Dar Gnawa?

Abdullah told me that one could not just decide to "become" a Gnawi (sbah Gnawi). A Gnawi endures a long process of induction, initiation and instruction. On the other hand, he said, there are people who are linked, martabit, to saints and spirits of the Gnawa pantheon. The word in Arabic comes from the root ra-ba-ta, to be linked or tied. "Randy Weston," said the m’allam, "came all the way from Brooklyn martabat, or linked to the spirit Sidi Musa and to the color blue." We know Sidi Musa as Moses, who delivered the Jews from slavery in ancient Egypt and into freedom. When I asked Randy Weston if he remembered his first encounter with Sidi Musa he said, "Yes, I remember very well…It was one of the most incredible musical experiences of my life. I had an experience really African. I heard the string instrument out front. Like having an orchestra and having a string bass as the leader. And I heard the black church, the blues and jazz all at the same time. I really realized that we're just little leaves of the branch of mother Africa." There are links between the pantheon of spirits in Morocco, who, like Sidi Musa, are ancestors, and the ancestors of jazz. One clear contiguity is between the slaves that went to the Americas and those who stopped earlier in the journey, at the tip of North Africa. Commenting on the lack of a written record of history, Abdullah El-Gourd told me that the slaves in Morocco would go through the city singing certain songs, songs known only to them, in order to be reunited with their loved ones that had been separated from them in slavery. "There were no telephones, then," he said jokingly, "no portables (or cell phones). Slaves had their own language in song. When they would come into a new city, they would sing the songs, trying to find their own." Songs served as auditory icons of identity, as sound "links". Weston found such a link to Africa in Morocco. For Weston, Africa is the source (to invoke Abdullah El-Gourd’s term), the birthplace, the mother of all traditions. Encountering Sidi Musa was also an encounter with the great jazz masters, however. What’s more, it was an opening into a different mode of being in the world. "When I heard this particular [version of] Sidi Musa, after the ceremony I was in trance for about a week. And when I say trance, I was functioning… I was moving, but the music took me to a very high level, it took me to another dimension…" There is an inversion, as well as a complementarity to the way Abdullah El-Gourd and Randy Weston define and pay homage to the ancestors. Both acknowledge the source in Africa itself – Abdullah El-Gourd by invoking the ma‘llemin (pl.), the early Gnawa masters that left their legacy to the present in the bodies and songs of those who possess tagnawit today, and Randy Weston by making frequent reference in his performances and presentations to mother Africa – the place – also defined as the "source" of musical and spiritual tradition. When I asked Randy Weston, for example, what he found so powerful about Moroccan Gnawa music he responded, "It’s like after being away from your parents for a long time, your mother and father, whom who love very deeply. And you know they are there, but you may never see them, or maybe you have seen them but you’ve been away a long time, when you do see them and you realize that what you have they gave you, you become very humble…" For Randy Weston, however, Africa becomes the primary place of return, whereas for Abdullah El-Gourd, at least in Dar Gnawa, the ancestors that crossed the Atlantic become primary symbols of genealogical display. These ancestors – African-American jazz men – are, we can postulate, just as tied to Africa (martabtin) as Mr. Weston himself – possessed, or inhabited by the spirits of Africa who know no spatial limitations, who don’t recognize borders, who are, in effect, outside of time.

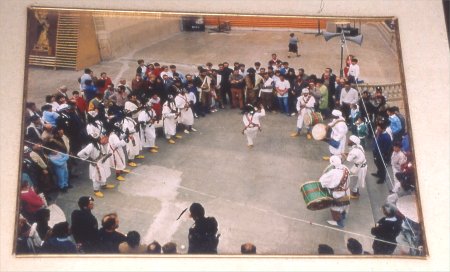

As I mentioned, there are a few pictures of the older masters of Gnawa – Ba Masud and Ba Hamid The visitor also sees the history of Abdullah Al-Gourd’s career as it took him and his musicians to Spain, to France and to the United States. These last images are like postcards sent back home from abroad. They are not images for export; rather they document "there" in the "here" of Dar Gnawa, a self-reflexive display of cultural tourism as enacted by the Gnawa (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998). The photos are emblems of internationalism at the level of the local

|

||||||||||